Welcome to the first installment of Paulina Day, a monthly missive drawing from the constellation of stories surrounding the ever-evolving art/life work, Paulina. If you follow along, you will likely find echoes of your story here too.*

I’d like to begin by addressing this story’s first big twist — something so essential to its larger meaning that it overrides any impulse to keep it secret.

It occurred about a year and a half after I found Paulina's 1945 testimony...

It was the fall of 2018. I had just relocated to Poland to investigate Paulina's story when I learned that the woman whose testimony I had uprooted my life to research, was not the woman I had believed her to be1.

Who was the Paulina I had thought I was following? ... The "other" Paulina?

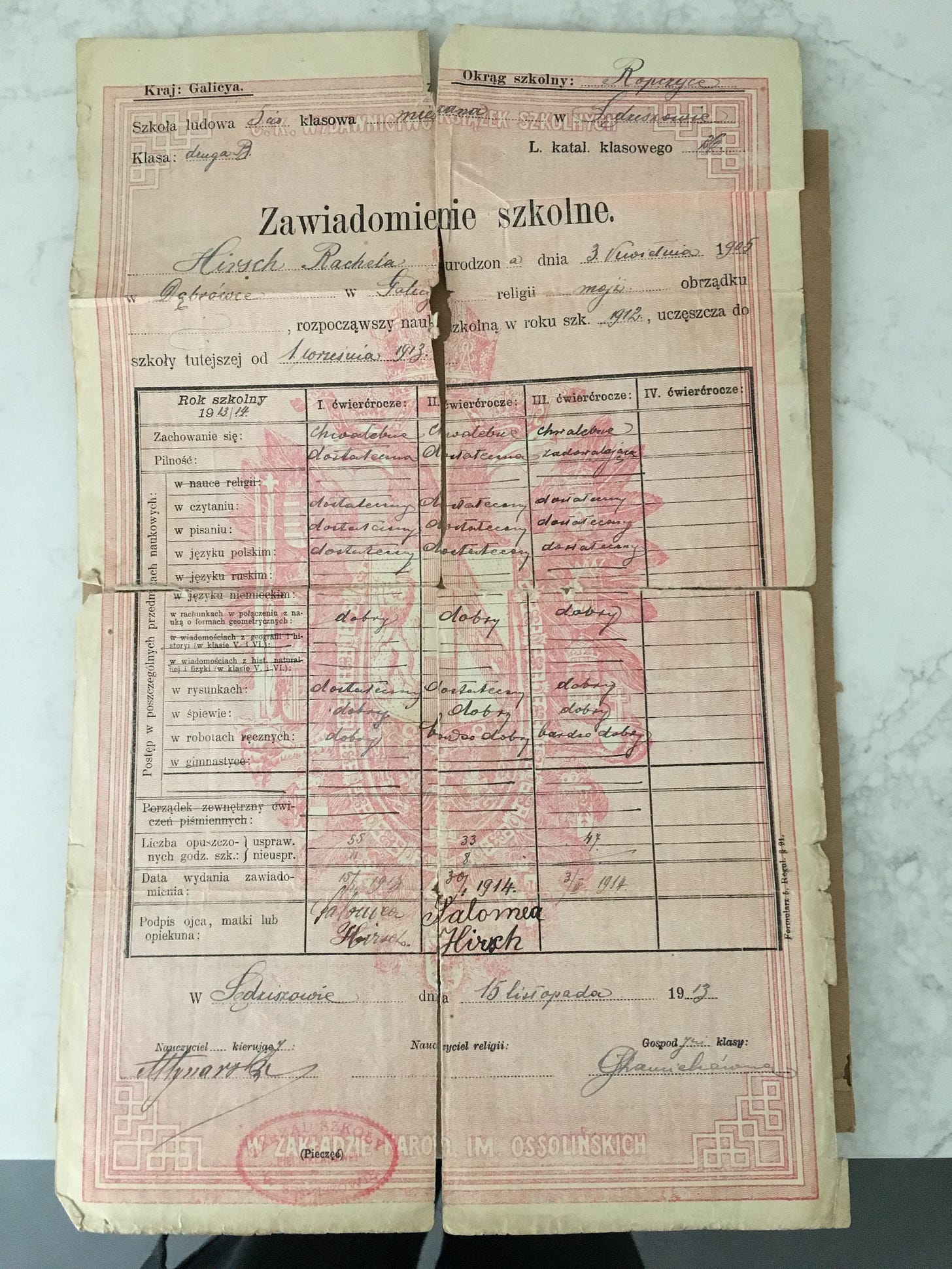

Born in 1902 in Krakow (same as my heroine, Paulina), the “other” Paulina was the recently discovered first cousin of my maternal grandmother whose family fled to the US during WWI. I had a special connection to my grandmother. After she died, I felt an urge to find her elusive birthplace – somewhere in the former Austrian Empire. There were no records or clues. But my mother, spurred on by my mission, spotted a crumbling paper in her files that she had not noticed before. A 2nd-grade report card from a Polish folk school in 1914 – my grandmother’s! It revealed that my grandmother was born in a small town called Dabrowa, now in Southern Poland. Most hauntingly, was an unfamiliar signature toward the bottom, in a field designated mother or guardian,

Salomea Hirsch. This was my grandmother's mother. A name that had been lost to time. Suddenly before us is the one single trace of the woman whose young death was so traumatic for my grandmother (who lost her mother at 11) that I still feel its effects. As the last in my unbroken line of mothers and daughters, I needed to give shape to this woman, my great-grandmother, who had been unjustly erased from my past. My search led me to a genealogist at Warsaw's Jewish Historical Institute who found nothing further on Salomea, except that she had a brother who stayed in Poland. He had a daughter, Paulina. This Paulina was at the time, "real" Paulina.

Are you with me so far?

Michelle yearns to find grandmother’s birthplace —>

Mom unearths Polish report card containing signature of great-grandmother’s previously unknown name Salomea Hirsch —>

In the absence of anything more about Salomea Hirsch, Michelle discovers the existence of great-grandmother Salomea’s niece, Paulina Hirsch.

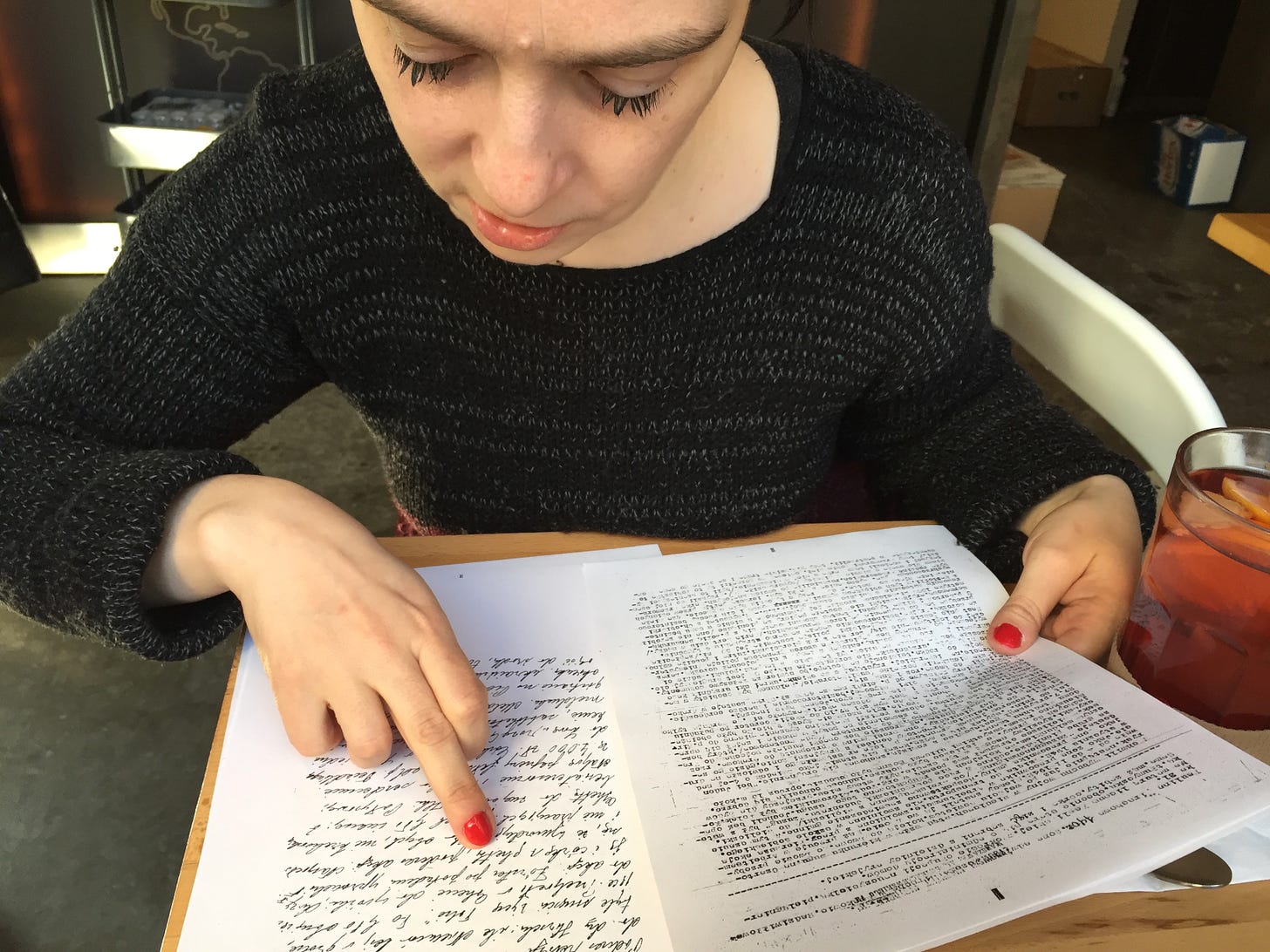

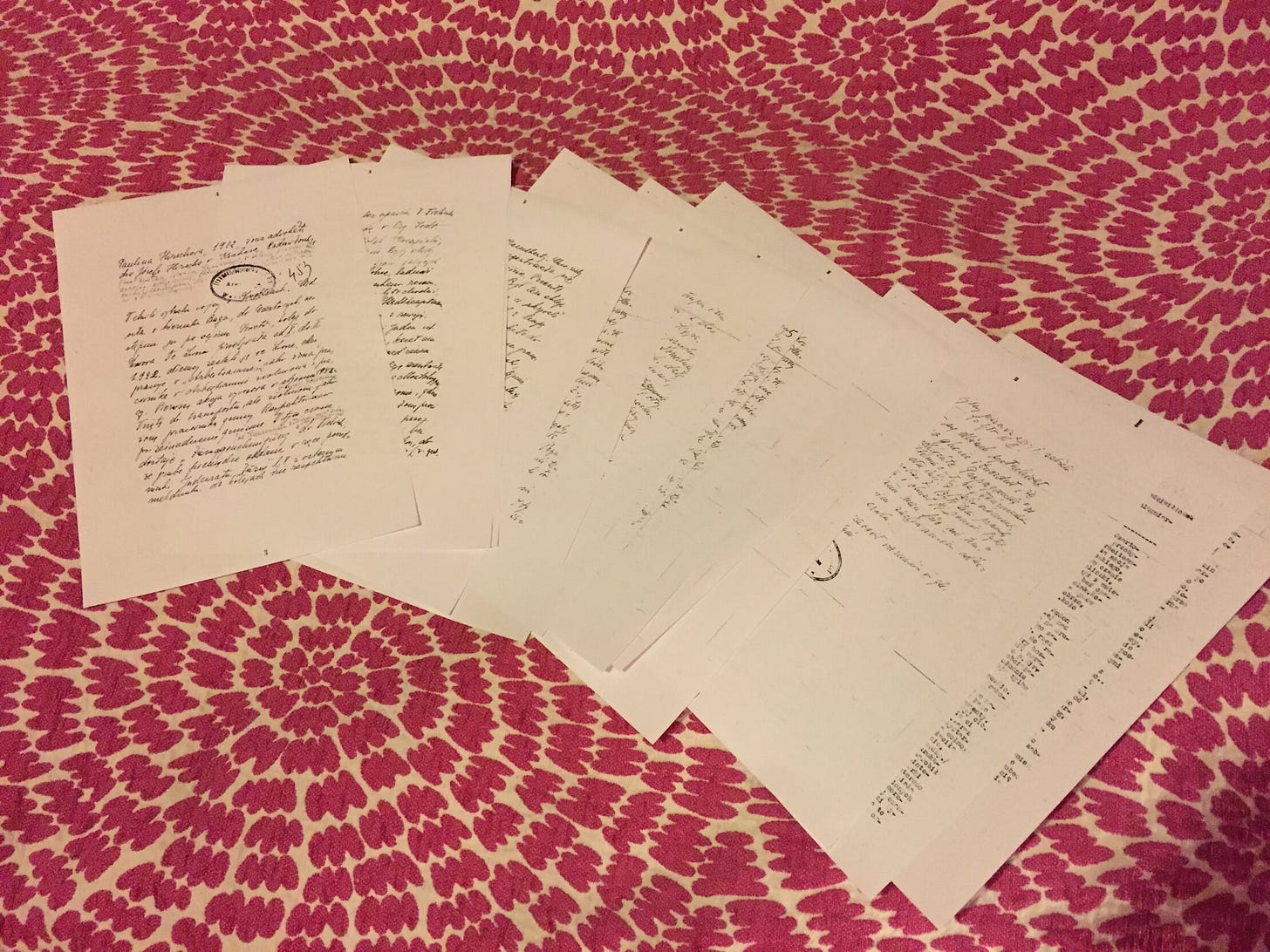

Once we had Paulina’s name, the genealogist did some typing into various databases and informed me that Paulina had survived the Holocaust and that a manuscript of her testimony – one of many collected by a Polish Jewish Commission at the end of the war – was on file in this very institution where we sat2. Within minutes, a copy of the Polish written manuscript was in my hands. I immediately appealed to Patrycja Dołowy (my future collaborator) with whom I had connected days before, to help translate it for me. The next day, the two of us experienced a profound moment together, captured under the spell of a thrilling survival narrative of a woman moving from city to city, hiding in plain sight. It was so full of suspense and twists that it read like the plot of a film that swung open a portal to the past, beckoning us to enter3.

I saw Paulina’s story as a proxy for the stories of the women in my family that remained untraceable. She represented the flipside of the coin, having remained in Poland long after my grandmother's family fled to safety in the US. She was my grandmother’s age in life and my age — 41 at the time — during the middle of the war. Patrycja, arguably my living flipside, was Paulina’s age at the start of the war.

It wasn’t until I had left behind my career and life in New York to dedicate myself fully to Paulina’s story, and until Patrycja committed to collaborating with me on a physical retracing of Paulina’s wartime path across Poland and Ukraine, that I learned the truth: Hirsch was this Paulina’s married name ( no, she didn’t marry a cousin with the same last name). My relative, Paulina, was born a Hirsch. This was such a simple oversight, it is remarkable that it was missed for so long by everyone helping with research and translation, but most of all, by me.

We see what we want to see.

The psychological conditions behind the error

At that moment of the discovery (February 2017), the world was shifting rapidly toward right-wing and autocratic rule. Poland was already years underway and Trump's administration had just begun, with essential rights being threatened and retracted with each passing day, echoing the previous fascist turn. In a moment where I felt I was teetering on insanity, I desperately needed something to grab onto and follow. Paulina’s text sparked a desire and a sense of possibility.

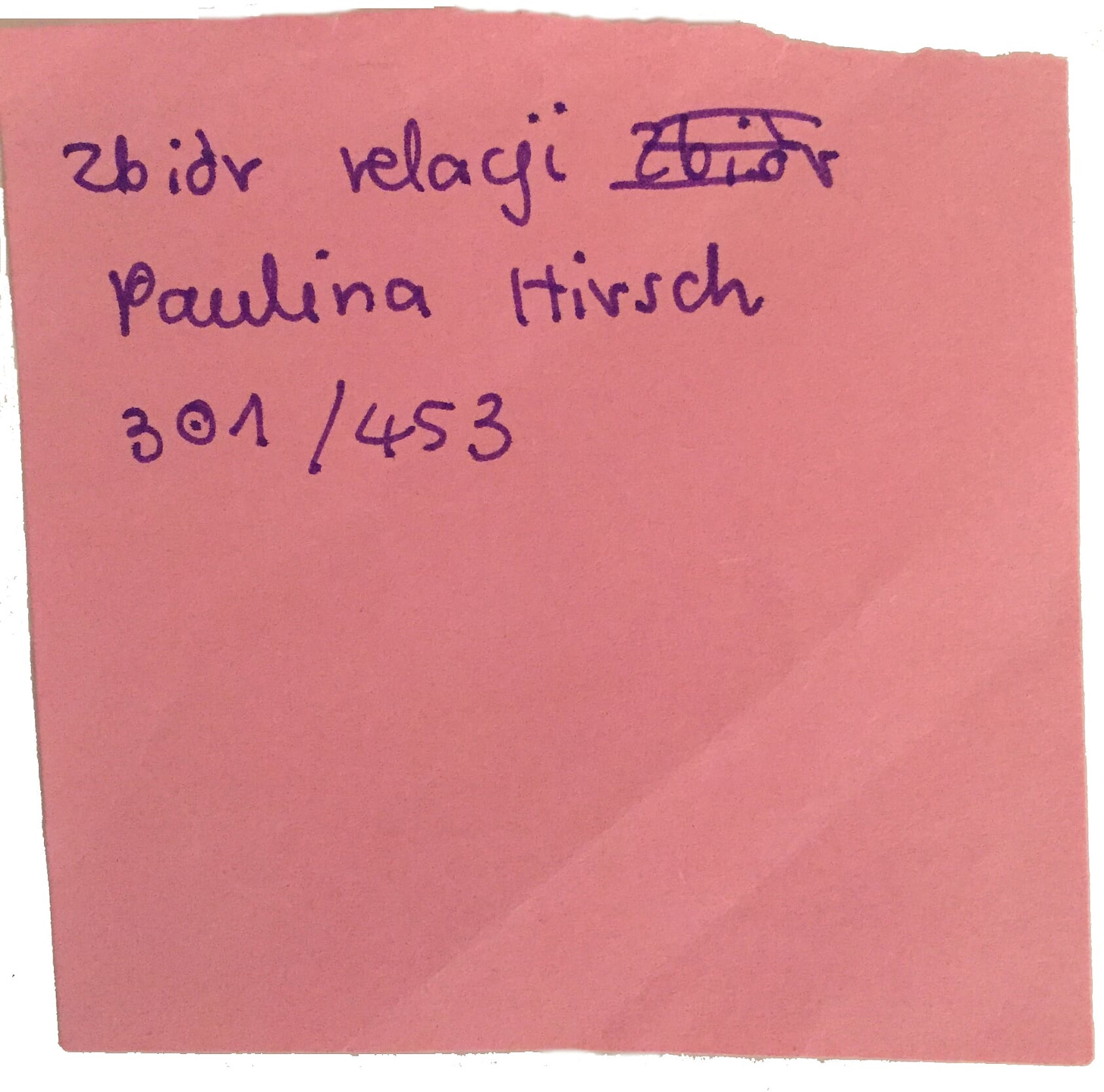

Maybe the genealogist also felt this, because when she gave me the above post-it to retrieve the document from the archives upstairs, why didn’t she emphasize that this testimony might belong to my relative? How could a professional genealogist, knowing how many names are mistaken for another, leave the question mark out, especially with a name as common as Hirsch? We had, in fact, just been through a whole involved process of determining which of the three Salomea Hirsches from Dabrowa was my great-grandmother!

Upon my recent visit to Warsaw, I met with the director of the genealogy department at the JHI to reflect on this blip in the story.4 She commented that while genealogists should remind us of the doubt that is always there in the findings, the hope and desire tied to an individual’s search for family is powerfully infectious. If the genealogist is young, as mine was, if she connects with her client, as mine very well did and as I did with her, (we bonded over the fact that we each wore our grandmother's ring) such well-meaning misdirections happen.

Had I been told right away, this could be your relative, how would that have impacted the outcome of this story?

My belief that this text came from a woman in my family created a profound elation, like a new birth. This feeling, delusional or not, drove me to care for the story. I saw Paulina as the counterpart to my grandmother. I imagined they had similar traits – fair features with bold, personalities, offering a clue to how Paulina survived on her own throughout Nazi-occupied Poland. I supposed they even played together as children, and my grandmother grew up wondering about her cousin across the ocean. These assumptions created an enchanted gateway into Paulina's text. Doing right by it became my primary focus in life.

I am grateful for the genealogical blip and that the order of things happened as they did because I and everyone involved needed to believe Paulina was my relative, for the future events to unfold as they did. I had to believe Paulina was my grandmother's kin just as Patrycja – with whom I had first bonded over the connection to our grandmothers – had to believe she was helping me shed light on my ancestor's story. Until we were so committed that it made no difference whose relative Paulina was. It was more compelling that she had no living descendants to tell her story.

When I finally discovered that my connection to Paulina's text was accidental, I understood its real agency – one driven by chaos and coincidence (and perhaps other forces too). Letting go of that connection to my grandmother involved some grieving and sadness. But in place of that was something wild and uncertain, a decision to trust a story for no other reason than that it is the one story that came out of the woodwork and landed in my lap.

What follows is a crazy adventure with twists and turns so unbelievable they sound like the plot of a film. Or a fairytale. Or a ghost story. With powerful revelations and connections between people across generations who would otherwise be strangers.

(The rest of that story is to come. )

With Paulina’s real identity uncovered, I could learn more about her life after the war. One discovery was that she eventually remarried, moved to the US, and died in Philadelphia. We visited her grave when Patrycja was on a recent trip to the US. At first, we couldn’t find it. The plaque was completely hidden under dirt. But we located and cleaned it, revealing our friend.

My great-grandmother’s grave is yet to be found. Oh, how I have searched and searched. My grandmother, due to nightmares associated with her mother’s death, was cremated. Paulina’s is the one grave that I can visit. And Patrycja and I are the only living family – in a very long time – to come and pay her respects.

Thank you for reading this reflection on intergenerational healing inspired by the experience of caring for stories of those who can no longer speak for themselves, creating a vision of the vastness of what family can be.

*Requests to readers:

Do you have a story about mistaken identities connected with family, genealogy, or archival research from which you learned something unexpected?

Are there any experiences this story brings up for you connected to a sense of absence/loss in your family?

I am still looking for anyone connected to my heroine Paulina. Though she had no more children, her second husband, Jacob Klinger, had a brother in Philly, Max, married to Tibie. They had two daughters, Linda Moran and Ester/ Starr Weiss. Paulina and Max Klinger moved to Philadelphia in the 1950s. Paulina died in 1991.

I am also looking for anyone connected to my relative Paulina Hirsch who was married to Josef Himmelblau and had two daughters: Edith and Bertha. They immigrated to the US via Belgium in 1942. A census places them in Manhattan in the 1950s. Edith may have had a daughter named Toni. The family may have eventually moved to New Jersey.

Please share your responses in the comments or reply to this message. Any of these responses may (with your permission) end up folded back into this project and make their way into the film. Thank you!

Poland’s Central Jewish Historical Commission’s main objective was to document the Holocaust, so it immediately began collecting testimonies from survivors at the end of the war. See https://www.jhi.pl/en/collections/archives

Patrycja and I met as two artist participants in Asylum Arts and POLIN Museum’s 2017 Poland Retreat for international artists interested in Polish Jewish History, hosted at POLIN in Warsaw. (POLIN later hosted my artist fellowship in Poland to research Paulina’s testimony, and Asylum funded the performative journey Patrycja and I took across Poland and Ukraine, following Paulina’s wartime trajectory.)

Anna Przybyszewska-Drozd, Jewish Genealogy and Family Center, Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute.